Image Credit1

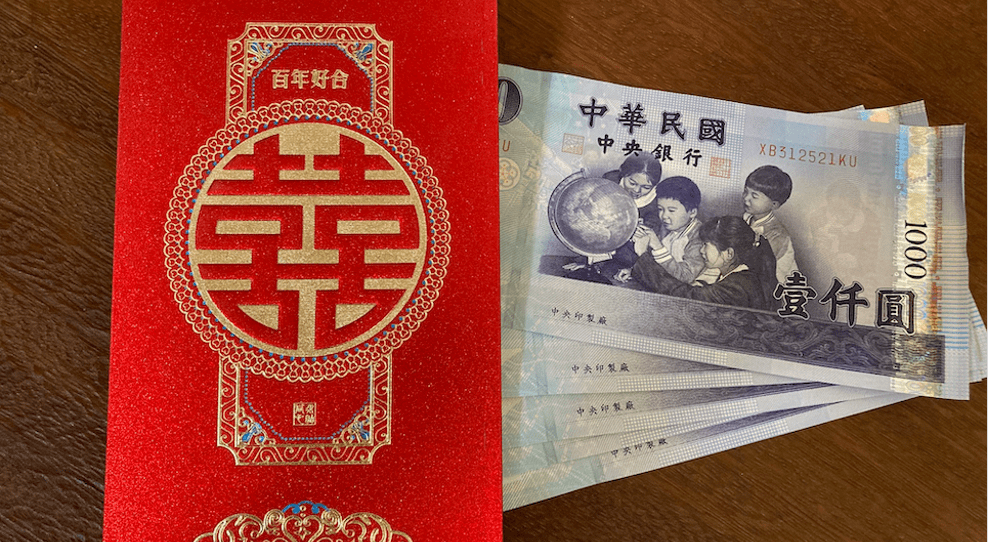

An implicit intergenerational care contract within families is more noticeable when you observe it in another country. Interestingly, in Taiwan, showing care through money is more explicit and embedded in the culture. About one-half of adults in Taiwan give money to their parents, and about a quarter of the parents give money to their children.2 Children start giving cash gifts when they begin working, and the amount increases as their salary increases. One working mother (I will call her TW15) gave red envelopes to her parents every Chinese new year starting at age 25–the amount ranged from NT$6,000 to NT$8,000 NTD (NT$30 = US$1). When her parents’ house flooded one year, she gifted them $NT50,000 so that her parents could buy new furniture. Now, at 54, she gives her mother NT$20,000 for the Chinese New Year, NT$8,800 for Mother’s Day, and NT$6,600 for her birthday.

Another working mother (TW1) started giving NT$6,000 per month to her parents at the age of 22. It was a symbolic gesture of gratitude, according to her, as she had grown up seeing her parents give money to her grandparents. Once her parents retired and could not sustain themselves, she gifted them NT$20,000 per month and paid for their private health insurance. Paying approximately US$8,000 per year (in addition to paying their private insurance fees) is a substantial amount; it is more than enough to fund one’s Roth IRA per year. Moreover, as is typical in many households, TW1 husband also contributes a portion of his salary to his parents.

This intergenerational care contract recognizes the importance of money in a way that is less explicit (and perhaps a looked down upon way as we are supposed to be a pull ourselves up by our bootstraps kind of society) in the US context. Major holidays and life events will always see red (or white in the case of a funeral) envelopes with crisp cash. There is something rather efficient about this method. I remember trying to put together a gift registry with my soon-to-be husband at Macy’s in Syracuse–after two hours, we managed to scan four items. How could we decide on the fancy dinner plate set? Even after 18 years, we still don’t have that set–(hello, Cristian, I’m ready for that set!). Indeed, as I had a Taiwan relative look over my interview questions for working mothers, she immediately noted that I had to define care not only in terms of food, clothing, housing, and management of the household but also in terms of financial help.

Image credit3

Of course, the Taiwanese intergenerational care contract includes more than financial help. Approximately 30 percent of working mothers receive full time childcare help from extended family members, most often from parents or in-laws.4 Although TW1 provided financial help to her parents, her mother took over care responsibility of her children, and when she passed away, her father took over the care work. In another example, TW12 drops her son off at her parents’ place on Monday at 6 am and picks him up on Friday at 6 or 7 pm. In this 24 hour weekday arrangement, TW12 also gives her mother 20,000 NTD/month to help care for her son. In TW9’s case, she and her husband live with her in-laws and they take care of her child during the day while she works. For TW16, her sister-in-law takes care of her child while living with her parents. TW16’s mother is in charge of cooking for the extended family after she comes home from work. Even if the working mother uses a daycare, as in the case of TW3, her mother will often let herself into TW3’s house and put homemade meals in her refrigerator with labels.

Caring for one’s child is a big ask of one’s family members. A good care contract, as I observe across my interviews of Taiwan working mothers, includes familial caregivers voicing their limits and “careneeders” respecting those limits. For TW11, her mother was willing to care for the first child but not the second; TW11 therefore had to find a 24 hour nanny for the second child. For TW17, her mother, who lives downstairs from her and is still working, refused to take care of her child at any point during the week but is willing to cook for the family after work.

In addition to adhering to boundaries, mutual respect and communication help to sustain the intergenerational care contract. In TW12’s case, whose mother takes care of her child 24 hours from Monday through Friday, if her mother wants to introduce a new food, she will consult TW12. In return, TW12 will also consult her mother for advice so that there is mutual cooperation in raising the child. A sense of gratefulness infuses many of these contracts.

Of course, parents/in-laws caring for children cannot work if they are too old (and this is more the case with women having children later) or if they live too far away. It also works less well when the mutual respect component is missing–TW12’s mother-in-law and TW4’s mother tended to be overly critical of the working mother’s mothering skills or had expectations of obligations (e.g., needing to cook meals over the weekend) that were too burdensome.

In the end, the above elements are probably found in all cultures with Taiwan accentuating some elements and not others. The themes of intergenerational care that are sticking with me are the ways in which money is a way of showing care and how the underpinnings of boundary drawing and mutual respect, both of which help to keep one’s negative emotions and frustrations in check, are levers to ensure a strong work-family balance in Taiwan.

1 The red envelope has the marriage symbol on it, and the gift is for my cousin who recently got married.

2 Chin-Chun Yi and Chin-Fen Chang, “Family and Gender in Taiwan,” Routledge Handbook of East Asian Gender Studies, NY: Routledge, 2019, 222–23.

3 Jonah With Grandparents by Wellwin Kwok/Flickr, license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

4 Interview with Chyn Yu-Rung, General Secretary of the Awakening Foundation, August 29, 2023.