“If I had to do an errand, I would walk out my door and yell to a neighbor to look after my children,” my aunt casually remarked about what it was like raising her five children in Taiwan in the 1970s.

I immediately imagined an apartment complex with mothers hanging out by their open windows, and one shouting out, “No problem!”

In this neighborhood, there were enough children to play together—older ones keeping an eye on younger ones, with competent adults nearby in case of emergency. It seemed that the more children a community had, the more built-in caregiving support existed.

Contrast this with Yu-Chen Qiu’s situation five decades later. At one point during our interview, she lamented that it was difficult to get help as a nuclear family—her supportive parents and in-laws lived about a 90-minute drive away.

“Can a neighbor take care of your child when you’re in a pinch?” I asked.

She shook her head. “I have no neighbors.”

“No neighbors?” I asked.

“I have no neighbors with children,” she clarified. “They don’t have experience with them.”

Yu-Chen’s situation wasn’t unique. A staff worker at my research institute described a more desolate scene in her neighborhood just outside Taipei, prompting me to imagine a lonely street with no one looking out their windows and no squealing children running down it.

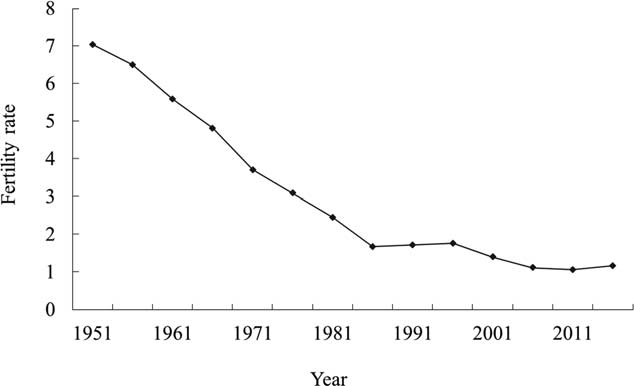

These childless neighborhoods appear to be the new normal. The graph below reveals the nosedive in the fertility rate of women of childbearing age in Taiwan from 1951 to 2014. Within the span of thirty years (1951–1981), the fertility rate fell from seven children to two, and then to around 1.5 in the 2000s. This precipitous drop is mirrored in my own extended family. My mother comes from a family of eight, and my father, a family of nine (with one brother passing away at a young age). As part of the second generation, I have one sibling and around 35 cousins. In the third generation, however, my children each have one sibling and a mere two cousins.

What Happens When the Community Disappears?

When I ask my Taiwanese working mothers about community today, they often reply that they have no time for community, or they reformulate the question into one about self-care—squeezing in an exercise class when they can.

Ya-Wen Xu volunteered for her son’s middle school yearbook, imagining creative moments with the middle schoolers and collaboration with other parents who had enthusiastically signed up. Instead, her experience felt more like a nightmare—she did it mostly alone while others begged off. She vowed NEVER to volunteer for such projects again.

Contrast this with an older mother I interviewed, who raised her children in the 1990s. Chia-Yi Lin noted that on Saturday mornings, from 8 am to noon, families came together, taking turns caring for children while also providing organized activities, varied according to the parents’ interests. One would spend time helping the children memorize classical texts. Others would teach Chinese knot-making, life skills, and tell stories from history. Chia-Yi took photos and organized excursions.

I am reminded of Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s research that men will help out more with childcare when there is more built-in support. Ironically, when care work is more pressing, urgent, and potentially overwhelming, they do less, as in the case of yearbook fathers and mothers as well.

For a myriad of reasons, women in rich democracies are having fewer or no children at all, resulting in neighborhoods that are losing care skills. The distance between my aunt’s window and the staff worker’s empty street represents the unraveling of a taken-for-granted care infrastructure.

In thinking about the US, when the Trump administration promotes IVF access or proposes a $1,000 birth bonus by opening a Trump account, the focus is on helping people have children. But what my interviews reveal is that we’ve lost something harder to recreate: the neighbor who shouts ‘No problem!’ from her window, the streets full of children playing and looking out for each other, the Saturday morning parent collective that made care feel less isolating and more communal.

Leave a reply to freepleasantlyfce936694e Cancel reply